Last month, I was lucky to have visited the Arkansas Art

Center with my mother to see their exhibition, Tattoo Witness:

Photographs by Mark Perrott.

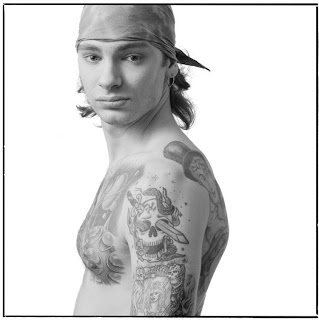

With countless black and white portraits of “tatted” individuals, this

exhibit encapsulates twenty-five years of tattoo culture from shops and studios

across the nation.

Perott captured images of tattoo artists and customers

alike, documenting the artistry of the tattoos and the stories of the people

who wear them. He is immortalizing

an ephemeral art that otherwise would only last a single generation. Each portrait captures a moment in the

subject’s life, as they proudly display the markings that set them apart from

the rest of the world.

Throughout the gallery, there are images of men and women;

old and young; business and casual; clean and dirty; black and white and

everything in between. The exhibit

challenges the viewer to question their preconceived notions of who gets

tattoos and why. Is a tattoo a

scar that mars your body for the rest of your life, or is it an expression of

your deepest passions and desires?

Is it a mark of childhood or a statement on trials you have

overcome? Does it show that you

are a part of an elite club, or is it simply a way to display your love for

artistic expression? Is it a means

to remembering an important moment or a lost friend? Is it a symbol of infinite love? Is it a call for attention or a means of blending in?

In many ways, he illustrates the connection between the

public and private nature of tattoos. What a person does with their body is most often a

personal choice. By permanently decorating

your body, you are making a choice to alter your appearance for personal

reasons, of which could be any number of things. Many times we are making a statement about ourselves or the

world, about our feelings, our likes and dislikes or our place in the life we

are living. These personal

reflections, no matter how conscious, are almost always factored into our

decision to make a permanent change to our appearance. That being said, in many ways, creating

an outward alteration by means of tattoo expression is a very public

presentation of our most private feelings. It simultaneously shows the world who you are while becoming

a part of your story.

Importantly, this exhibit brings people of various

backgrounds and histories together with a common bond of artistic expression

through a practice that has been around for thousands of years.

Incidentally, around the same time that I was exposed to

Perrott’s photographs, I also came across an article about a Siberian

‘princess’ whose body was found preserved in permafrost, keeping her 2500 year

old tattoos intact and easily observable.

‘Princess Ukok’ is highly decorated with images of mythological

creatures and intricate drawings that most likely exemplified age and status

within her people.

Like the tattoos that adorn our bodies today, her tattoos

seem to be as aesthetic as they are practical. The designs were placed carefully for viewing purposes,

drawing on the presentation and public aspect of tattoo custom. The body was, and is, another medium

for artistic, personal, and societal expression and have amazingly stood the test of time.

Our cultures are constantly changing and evolving, often

blending with those of others around us. These two incredible examples of body art as a means of expression and

symbol, each representing a vastly different civilization, really show that no

matter how much people think we change over generations, we still employ many

of the same practices that have defined us for thousands of years.